Migration Marvels Part 2: Birds without Borders

Migration really is one of the world’s natural wonders! The sheer magnitude of some of the journeys undertaken is enough to make even the most adventurous traveller green with envy, with some birds visiting 20+ countries on their annual return journey. It makes me think back to my first blog where I spoke about an encounter with a pair of Wheatear on Barossa. The timing of their arrival made them likely candidates for the Greenland race of Northern Wheatear. These birds had probably already travelled all the way from Central Africa somewhere and were just using Barossa as a pitstop before doing another 2000+ mile stint to Greenland or even to Northern Canada!

Our heathland birds have a range of strategies when it comes to the migration period. Some like the Dartford Warbler don’t migrate at all or at least don’t go very far, taking advantage of the decrease in competition and the mild winters of the UK. This of course carries some risk. Being entirely insectivorous, a harsh winter can easily wipe out populations, but it does mean they don’t have to franticly build up fat stores for a long trans-continental journey. Birds such as our Woodlark and Meadow Pipit will also mostly stick around the UK over winter, but some will undertake a relatively short migration to the continent, either France or the Iberian Peninsula depending on conditions in the UK. Whitethroats, Redstarts and Tree Pipit are all true summer visitors and will begin the annual journey to sub-Saharan Africa within the next month or so, returning between late March and early May. Hobbies, like Nightjars, are true long distant migrants and will spend their winters in tropical Africa. The exact location is still a bit of a mystery, although two birds, fitted with satellite tags, that spent the winter months on the southern edge of the Congo rainforest, in Angola, might hint at the winter location of some British Hobbies.

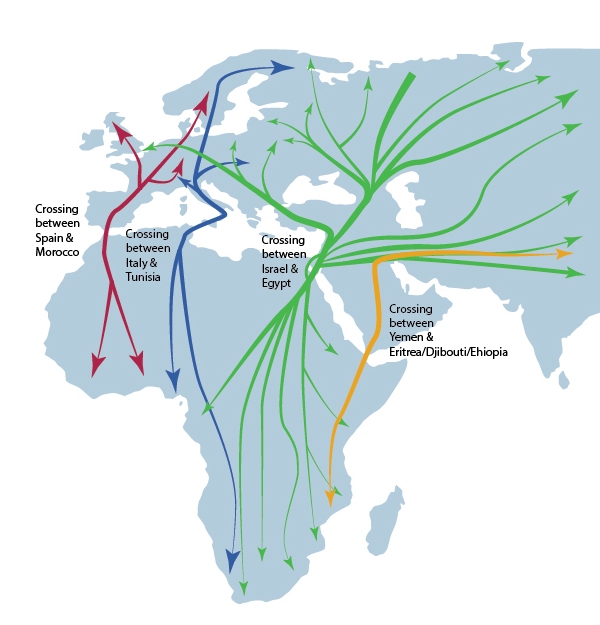

Birds travelling from Europe mainly take three routes: the Western route via Gibraltar is probably the best known. Most of our migrant birds will take this route, travelling down through Western France, across the Pyrenees, down into Spain and across the strait of Gibraltar into Morocco. The Eastern route goes across Eastern Europe (the Baltics, Belorussia and Ukraine) across the lower Caucasus’s mountain range through Georgia and Turkey into the Middle East, eventually crossing into Africa. The third route is often forgotten, but is no less important. It is known as the Central European migration route or Adriatic Flyway and runs parallel with the Eastern route, but bears westward over Poland and Hungary down through the Balkans and over the Adriatic sea towards Italy, before passing through Sicily and Malta before reaching Northern Africa.

Warden Conor

A simple map of migration routes